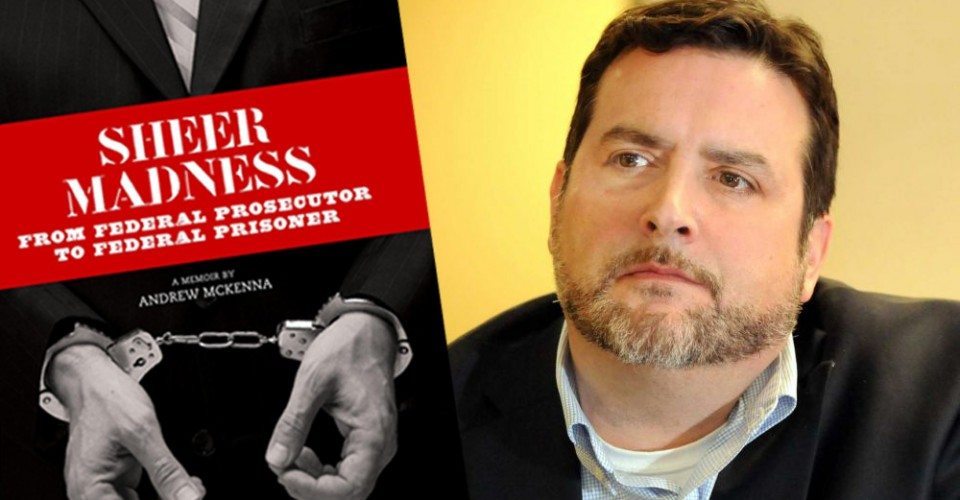

Andrew McKenna Shares Story of Hope and Redemption

Former Federal Prosecutor Breaks Silence After Nearly 6 Years in Prison

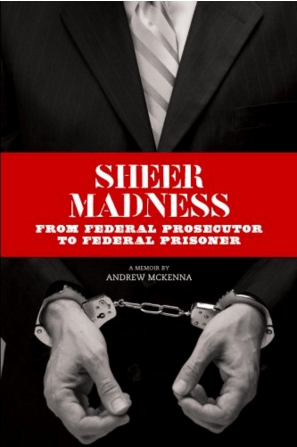

ALBANY, New York (March 21, 2016) – What force can drive someone with a successful career in criminal justice, a wife and three children, and a seemingly perfect life to leading a double life of robbing banks and eventually withdrawals on the floor of a jail? It’s one of the many subjects discussed in Andrew McKenna’s Sheer Madness. What began in the pages of a composition book behind the bars of a federal prison has now become what critics call a “tragicomic masterpiece” that you “absolutely can’t put down”. While working on his second memoir, McKenna, who now lives in upstate New York with his wife Dawn and their children, sat down with Vertava Health to give us entry into a world of processing cases by day and stealing money and shooting up on the bathroom floor by night. Now a legal advocate for a local law firm, McKenna met us at Angelo’s 677 Prime in the heart of New York State’s capital to tell us his story of a time in his life that blurred the line separating both sides of the law. For more of our interview with Andrew McKenna, check out this video.

The Early Days.

“Growing up I was always a bit of a risk taker,” says McKenna. “I didn’t feel 100% comfortable in my own skin as a teenager. Although outwardly everything looked fine, inwardly I didn’t feel great.”  McKenna says he grew up with many insecurities, and looking back it was more than just teenage angst. Depression, mental health issues, etc. As a way to cope with that, he found that if he drank beer and smoked pot, he wouldn’t have those feelings anymore. Unfortunately, doing that, he never developed the coping skills he needed to properly deal with those thoughts and emotions in effective ways. “That’s when I first realized I could self medicate and feel better about the world,” explains McKenna. “Of course, we know that’s a house of cards, and it can’t be sustained.”

McKenna says he grew up with many insecurities, and looking back it was more than just teenage angst. Depression, mental health issues, etc. As a way to cope with that, he found that if he drank beer and smoked pot, he wouldn’t have those feelings anymore. Unfortunately, doing that, he never developed the coping skills he needed to properly deal with those thoughts and emotions in effective ways. “That’s when I first realized I could self medicate and feel better about the world,” explains McKenna. “Of course, we know that’s a house of cards, and it can’t be sustained.”

A Life Changing Injury.

McKenna was an extremely high achiever. After college and law school, he entered the Marine Corps. Judge Advocate General Program. It was there, during a training mission for night land navigation, where he fell down a cliff and hurt his back. He says at the time, in the Marines, you couldn’t go for proper treatment. “They would either just send you home and essentially end your career – or at least this was my perception – or you were sort of the bird with the wounded wing and were kind of left behind in training,” says McKenna. “So I just kept my mouth shut.” McKenna treated his injury with Motrin and heating pads for four more years in the Marines, until he went to work as a federal prosecutor for the Justice Department in Washington, D.C. No longer serving as a Marine, he very went to a civilian doctor to get pain medication for his back. That’s when he says he found the perfect doctor.

The “Perfect” Doctor.

“He started to prescribe oxycodone, hydrocodone, pretty much in the numbers,” says McKenna. “Whatever I wanted.” Ironically, McKenna worked in the Narcotics and Dangerous Drugs Division of the Justice Department, where the unit’s mission was to investigate international drug cartels and money laundering, indict them and get them extradited to bring them to justice. Young, up and coming, and getting better and better cases, McKenna says he was abusing prescription pain pills – living a double life. “You go into survival mode,” says McKenna. “You do what you can to get through to make it.” Ultimately, he left the Justice Department and moved back to upstate New York from Washington, D.C. From there, he went to a law firm in Albany, where he doctors denied him the same level of prescription drugs as he took in the nation’s capitol. McKenna says the transition didn’t help, because he wasn’t really happy in the law firm setting. At the same time, his marriage was facing trouble. “Now, not only was there the self medication component, but my craving for opiates had turned physical,” says McKenna. “The straw broke when I couldn’t get the doctors to prescribe anything, so I turned to an old friend I knew, and he got oxycontin.” McKenna had never tried it before – a completely different animal. He calls it, “Heroin in a pill.” Within just a few days of using oxycontin, he was completely addicted. When those ran out, he started to go through withdrawals. (Now, when he speaks to college and high school kids, McKenna explains it as having the flu – times 20. It was the worst pain he had ever felt.) When he called his friend to get more oxycontin, after screaming on the phone for about 10 minutes about feeling bugs crawling on his skin, his friend told him to come over. “I went over to his house, and he puts a little bit of heroin on a mirror,” says McKenna. “I had never used heroin. I’d seen it as a prosecutor, and I knew immediately what it was. And I did it. Immediately, the pain of the withdrawals went away.”

From Prescription Pain Pills to Heroin.

Within a few days of using heroin, McKenna was addicted to it. If he didn’t do it, he became physically sick. He tried to kick the habit by himself, because he didn’t want anybody to know. McKenna said he would make it through a day, but the vomiting and terrible feelings become so big – he’d spend $10 on heroin to make the withdrawals goes away. McKenna still says, it’s unsustainable. Eventually, after repeated losses in family court, he became despondent. He couldn’t see his two young boys anymore. The family court judge called him a “junkie” because it had all come out by this point. One day he was so sick that he called his brother, lying on the bathroom floor and covered in his own vomit. His brother didn’t tell his wife what was going on, and instead rushed him to the hospital, where McKenna went through a detox facility at a local hospital.

A Cycle of Addiction.

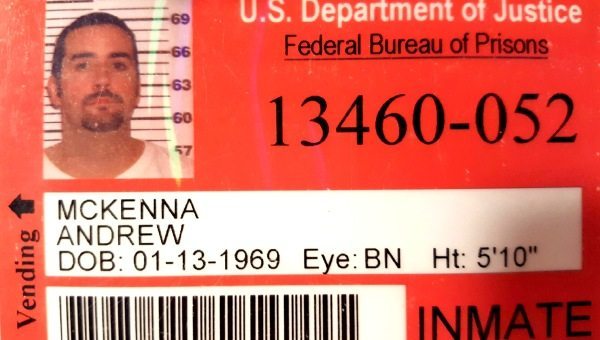

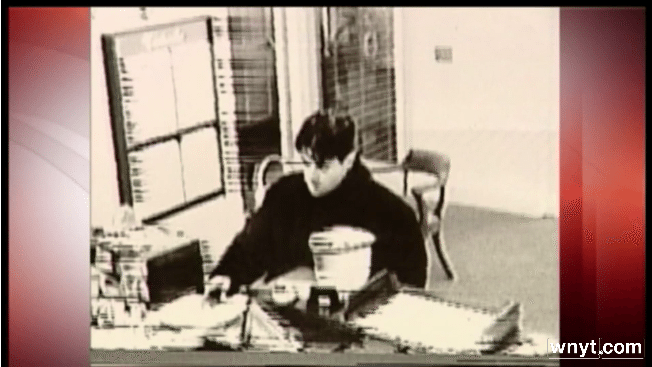

“I got into a 28 day [addiction treatment] program and was released,” says McKenna. “But 28 days isn’t long enough for opiates. And they recommended I go to 12 step meetings. Twelve step meetings are great for some people, but they’re not great for all people. It wasn’t a good fit for me.” McKenna says the 12 step programs weren’t enough for him. The withdrawals weren’t gone yet, and he still had untreated depression and no follow up from treatment. He relapsed. He wanted the pain, both mental and physical, to go away, and it was very easy to do with drugs. At this point his addiction was public. McKenna lost his job, due to the relapses, and still couldn’t see his children – even when he put together some solid months of sobriety. The family court judge was unrelenting, which McKenna says wasn’t that judge’s fault. “I wasn’t exactly the picture of hope standing in front of him in court,” says McKenna. “I get that. But I became angry, and despondent, and depressed, and all of these things came together. One day I was going to family court and knew I was going to suffer another loss.” That day, McKenna drove north to Lake George, went to the first bank he could find, and he robbed it. Over the next 6 weeks, he robbed 5 more banks and 2 grocery stores. Ultimately, he was caught. He recalls the tragic time. “I don’t blame anybody but myself,” says McKenna. “I was in the compulsion stage of addiction. I still could’ve asked for help.” McKenna says he believes 28 days isn’t enough recovery time for any addiction, especially opiates. He says the cravings can last for months. He says one of his regrets is not doing more than 28 days. He had never been to jail before, and was sent to the local county detention center, where he experienced withdrawal from the drugs on the floor of the jail. “Throwing up, vomiting, guards laughing,” says McKenna. “Worst experience of my life. Humiliating and miserable.” With bank robbery charges, McKenna says it took three tries to be granted bail, which included ankle bracelet monitoring, intensive outpatient treatment at a local facility, and meetings with psychologists. Ultimately, McKenna plead guilty to the robberies, and was sentenced to 65 months in federal prison.

Federal Prison.

“Initially we told the judge the robberies were to obtain drugs, which is what we believed at the time,” says McKenna. “But through therapy I kind of came to the realization in treatment that it had more to do with anger, frustration and depression. Anger at myself, anger at the system, whether it was misplaced or not. That’s what I was feeling at the time. I’m not a sociopath, so clearly I had just gone off the rails.” McKenna robbed six banks and two grocery stores in a 6-7 week spree. It was uncanny in the sense that he didn’t wear a disguise other than a baseball cap. On the nightly news he would see himself in the footage that was released from the banks to the press.

Lifting the Fog.

McKenna says his life was taken away from him and he was responsible: It wasn’t his ex-wife, it wasn’t the family court judge, it wasn’t his friend. He was responsible. Sitting in prison, day in and day out, knowing that if anyone found out he was a federal prosecutor, it wouldn’t be hard to off him, led Andrew to the pen. He started keeping a journal in a composition book behind the cells of a prison. “Once you get clean and sober, the fog lifts,” says McKenna. “All these people who loved you and how you have hurt them. I came to realize that if I held on to the guilt and shame of what I had done, and everything that had happened, I couldn’t be the best person I could be for them. It’s essentially victimizing them again.” McKenna says you have to forgive yourself, and move on with your life. It’s the best thing for you, and for those around you. A friend of his picked up his journal after he was released and encouraged him to finish it. The result? 306 pages that detail his journey from the courtroom to the jail cell, and what it means to be a survivor. His message for those battling addiction is simple: Get help. “You don’t have to be labeled an addict, you don’t have to carry that the rest of your life,” says McKenna. “There is life after your addiction. I don’t consider myself a recovering addict. I consider myself ‘recovered’. You have to grow and put your past behind you, but always be mindful of it.”  Sheer Madness is available on Amazon.com. For our full interview with Andrew McKenna check out this video. Thank you Andrew, for being a voice to those who desperately need it.

Sheer Madness is available on Amazon.com. For our full interview with Andrew McKenna check out this video. Thank you Andrew, for being a voice to those who desperately need it.